Location:

The area they inhabit, roughly 100,000 square miles, is sometimes referred to as Maasai land.

Population:

Language: Maa.

A Nilotic language that originates from the

Ancestry: Nilotes and Hamites.

Nilotes originate in the sub-Saharan northeast. Hamites originate in

Sustainability:

Livestock and Agriculture.

Traditionally semi-nomadic pastoralists, the Maasai have relied exclusively upon cattle for the majority of their diet. Modern day restrictions on grazing lands have forced some to take up farming on the side, if not entirely.

Religion: 75% traditional worship of Enkai or god.

25% Christianity

Authority:

Chiefs hold political control.

Laibons are religious leaders.

Elders resolve local disputes.

(Males only)

Subdivisions:

Twelve geographic subdivisions (where customs, appearance, leadership and even dialects may differ).

Keekonyokie, Damat, Purko, Wuasinkishu, Siria, Laitayiok, Loitai, Kisonko, Matapato, Dalalekutuk, Loodokolani and Kaputiei.

The Maasai are an ethnic African group of semi nomadic people located in

The Maasai are a proud warrior tribe who has scarcely changed their ways and dress over the centuries. The Maasai are said to have had such a fearsome reputation even the slave traders and European missionaries were deterred from trying to enslave or preach to them. The first stories that Europeans at the coast heard of the Maasai was of a fierce and warmongering people. The warriors of the Maasai, the moran, were the most feared in

According to Maasai oral history and the archaeological record, it is alleged that they originated from the north of

Today Maasai land covers a much smaller area due to land taken for European settlements in the Rift Valley and on the Lakipia Plateau during the colonial era, and later by African agriculturalists. The Maasai of the Mara plains in

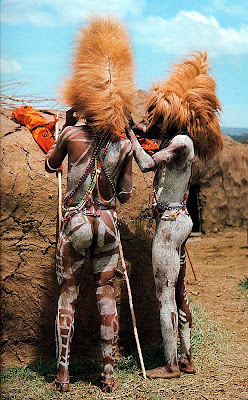

Maasai Warriors wearing hats made from the mane of a lion that they have each killed. When the warrior becomes a Junior elder he must throw the lion mane head gear away through a sacrificial event to keep off bad spirits

There are many ceremonies in Maasai society including Enkipaata (senior boy ceremony), Emuratta (circumcision), Enkiama (marriage), Eunoto (warrior-shaving ceremony), Eokoto e-kule (milk-drinking ceremony), Enkang oo-nkiri (meat-eating ceremony), Orngesherr (junior elder ceremony), etc. Also, there are ceremonies for boys and girls minor including, Eudoto/Enkigerunoto oo-inkiyiaa (earlobe) and Ilkipirat (leg fire marks). Traditionally, boys and girls must undergo through these initiations for minors prior to circumcision. However, many of these initiations concern men while women’s initiations focus on circumcision and marriage. Men will form age-sets moving them closer to adulthood. The movement of a person from one age-grade to the next marks the most important transitions in the life of an individual and in the wider life of the community. The Maasai age set system gives their society its structure.

Maasai families live in an Enkang a form of enclosure, stockade or kraal formed by a thick round ‘fence’ of sharp thorn bushes; this protects the tribe and their cattle, especially at night, from rival tribes and other predators. The Enkang may contain 10-20 small squat huts made from branches pasted with fresh cow-dung by the women which bakes hard under the hot sun.

Maasai huts aka Manyattas are very small, with perhaps two ‘rooms’ and not enough height for these tall people to stand upright or lie fully stretched. They are also very dark with a small door-way and tiny hole in the roof. The hole in the roof serves two purposes; it lets a little light into the hut but just as importantly it lets some smoke escape from the smoldering (cow-dung) fire which is kept alight for warmth and cooking - and perhaps to smoke off unwanted insects. The Enkang used to be ‘temporary’ and something that could be built elsewhere if the Maasai had to migrate to fresh areas of grazing, although such action is less feasible these days.

Women do not have their own age-set but are recognized by that of their husbands. Ceremonies are an expression of Maasai culture and self-determination. Every ceremony is a new life. They are rites of passage, and every Maasai child is eager to go through these vital stages of life.

Maasai most valuable possession is their cattle. The Masai believe that all cattle in the world belong to them, even though some may have temporarily found themselves in the possession of others. Thus, the Masai are always justified in raiding their non-Masai neighbours in order to “return” the cattle to the rightful owners. Cattle plays an integral role in the socio-cultural fabric of the maasai community. Furthermore living in the plains culture is dominated by cattle, as are their social relationships, their ritual and ceremonial life, their symbolism, and even the idioms of their language. At the heart of their respect for cattle lie strong economic and ecological truths. On the dry grasslands of

The value of cattle is also judged in social terms. There are good reasons for this. To spread his risk, a wise herder will distribute his animals among relatives, age mates and friends. Livestock are given as loans and in payments of a variety of social debts. If disaster should strike a man’s main herd he can at least hope to call in debts from others in order to start rebuilding.

The Maasai are a proud and independent people who have survived despite incredible pressures; however their greatest challenges remain ahead. They are losing their grazing land and losing their ability to roam freely throughout the country. Their people, especially the younger ones, are being influenced by modern schools and city developments. Some Maasai may seek comfort and income from the tourist industry by selling beads and craft-work, parading and dancing, opening their Enkangs for to the tourists however such income is not sufficient and such a way of life is not proper for these people. It remains to be seen how well they continue to retain their identity.

No comments:

Post a Comment